EXPLORE

Mazda CX-5 tours Vietnam

A bewitching blend of tradition and modernity, Vietnam has transformed itself from a country on the edge of collapse to one of increasing prosperity over the past 30 years. We find out how, and also drive Southeast Asia’s best driving road: the Hai Van Pass. Watch the video below.

Watch: Mazda CX-5 in Vietnam

The bravest citizen in Ho Chi Minh City is the honest traffic warden. Clad in helmet and protective gear against the hurricane of scooters and cars that swarm the streets, he faces a daily struggle to maintain order in the face of impossible odds. This is as inspirational as it is terrifying. The unprecedented chaos of driving in Vietnam’s second city is particularly apparent as I nudge our Mazda CX-5 through the humid morning air, intensely aware of the SUV’s pristine Soul Red Crystal Metallic skin as waves of commuters skim past on their way to work.

It’s early in the day, but Ho Chi Minh City is already ferociously busy. Architecturally, the city is a compelling mix of hyper-modern—the Bitexco Financial Tower an ever-present landmark—and French colonial past. Local shops and kiosks sell a variety of dishes, from aromatic pho soups to delicious banh mi sandwiches, and vie with global fast-food chains for business. The only (rather incongruous) reminder that Vietnam is a single-party socialist republic built on communist principles is the occasional red banner sporting the hammer and sickle.

Edging through this buzzing city, it’s difficult to imagine that 34 years ago Vietnam was a country on the brink of collapse, mauled by three horrific wars. The World Bank says that by the mid-1980s “annual inflation was running at more than 400 percent, the economy was on a downward slide, and the majority of the population in poverty.”

Yet today Vietnam has one of the fastest-growing GDPs in the world, a large workforce and low poverty levels. The country is considered a specialist in fostering start-up ecosystems. We’re in Vietnam to discover more about this astonishing turnaround, meet those involved in the nation’s recent success and take the CX-5 on a tour of the country, including the Hai Van Pass, one of Southeast Asia’s most legendary driving roads.

Our first port of call is RMIT University. The university’s Ho Chi Minh City campus is a modern construction crafted from concrete and glass. Over a cup of mint tea in an airy canteen, Dr. Trung Nguyen, Senior Lecturer at the School of Business and Management (pictured below), wastes no time in describing how the Vietnamese government went about rebuilding the country.

The story begins in 1986 at the Sixth National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam, held in the capital, Hanoi. It was then that the forward-thinking leadership, guided by freshly elected General Secretary Nguyen Van Linh, designed a range of economic reforms—called the Doi Moi—which was to act as a blueprint for Vietnam’s recovery. The aim was to open the country to the world.

Dr. Trung describes how the government was inspired by other Asian states (principally Japan, Taiwan and China) to produce a hybrid socialist-oriented market economy, allowing demand and supply to influence things, rather than communist policy. In 1987, the government passed a “progressive” law allowing foreign investment into the country, and a “significant milestone” was achieved in 1994 when the U.S. lifted its Vietnam trade embargo. After that the milestones came thick and fast.

“Extreme poverty fell from 58 percent in 1993 to 3 percent in 2015, and the average household income climbed from US$95 per year in 1990 to US$2,564 in 2018.”

The country subsequently signed 12 multilateral and bilateral trading agreements, joined numerous intergovernmental organizations (it is the chair of the 2020 Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit), and in January 2020 became a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. In 2019, Hanoi even hosted a meeting between former U.S. President Donald Trump and Supreme Leader of North Korea, Kim Jong-un.

With global rehabilitation has come significant foreign interest (the UN World Investment Report in 2018 put Vietnam in the top 20 countries for foreign investment). This, combined with careful domestic expenditure, has achieved an average GDP growth rate of 6.78 percent over the past 30 years which, according to the World Bank, is “among the fastest in the world, surpassed only by China.”

This growth has hugely benefited many Vietnamese people. Extreme poverty fell from 58 percent in 1993 to three percent in 2015, and the average household income climbed from US$95 per year in 1990 to US$2,564 in 2018. The World Bank estimates that by 2035 “more than half the Vietnamese people will be part of the global middle class.” Dr. Trung confirms that “people’s living standards have improved significantly.”

Vietnam has also established itself as a great place to form a business, with around 750,000 start-up companies in operation. To find out more about the start-up scene, we make a hair-raising dash across town to meet two entrepreneurs. The temperature has risen perceptibly and we are soon cutting through streets crammed with tiny shops selling everything from bicycle tires to white goods. It’s obvious that while Vietnam’s current growth has been manufactured by policy, this hasn’t created the kind of synthetic, sanitized city found elsewhere in Asia.

“You notice the enthusiasm here. There’s a heartbeat. One of the reasons I chose to start Soul Story here is that I fell in love with Ho Chi Minh City. It’s not perfect, but there is so much potential and people are hungry for success.”

Vivian Story, Soul Story Skincare founder

Vivian Story is the Korean-Canadian founder of Soul Story Skincare (pictured above, right), which produces cosmetics made from “high-quality, pure and powerful ingredients.” Julie Huynh, who is Vietnamese born (pictured above, on the left), but raised in California, is the Marketing and Operations Manager at Rita Phil, one of a handful of online companies that offer custom-tailored clothing for women.

Neither Story nor Huynh grew up in Vietnam, but both moved to Ho Chi Minh City to start their businesses. Huynh says she was attracted by the “levels of growth happening in Vietnam” and that Southeast Asia is touted in California as “the next hub” of the global start-up scene. This, combined with the ease with which you can start a business in Vietnam, made it an obvious move. She tells us: “The government is very willing to help domestic growth; it’s doing a good job. The barrier to entry is very low and the people are just so welcoming.”

Story agrees, adding the vitality of Vietnam makes it an inspiring place to launch a start-up: “You notice the enthusiasm here. There’s a heartbeat. One of the reasons I chose to start Soul Story here is that I fell in love with Ho Chi Minh City. It’s not perfect, but there’s so much potential and people are hungry for success.”

In early 2019, having met through the start-up scene, Story and Huynh launched The Beehive, a collective pop-up that promotes female entrepreneurs in Vietnam. Acting primarily as “a platform for distribution,” the group puts on quarterly events, where women sell their products, network and seek advice. It’s been a huge success, creating “a community spirit in a city where there is such intense competition,” and each event has grown in popularity.

As we part, Story makes the observation that Vietnam’s rise “goes together” with the success of the start-up sector. They drive each other, and “as people see more successful start-ups come out of Vietnam, it gives others hope that they too can succeed.” The result is a self-perpetuating cycle of success.

We only have a short time in Ho Chi Minh City, so we head for District 2 to watch the sun go down behind the city’s skyline, silhouetted on the opposite bank of the Saigon River. It seems that most of the city’s eight million scooters have had the same idea, and it’s a genuine pleasure to watch the locals—from businessmen and women to schoolchildren—mingling among the food stalls and enjoying the warm air. The ever-present clamour of construction provides the evening’s soundtrack.

The next day we head north to the coastal city of Da Nang, which has become something of a poster child for Vietnam’s expansion. With a vibrant food scene, beautiful beach and booming economy, it is attracting investment and tourism on a huge scale. En route I consider how Dr. Trung had been keen to point out that while Vietnam has come a long way in the past three decades, a number of challenges remain for the country. A scan of the World Bank’s 2015 “Vietnam 2035” report highlights hurdles the country has to clear if the upward trajectory of prosperity is to be maintained.

For a start, the demographic statistics are a cause for concern. While the current population structure means there is a huge number of people of working age driving growth, the population under 15 has fallen and in the future, there may not be the numbers to replace the ageing workforce. In addition, with a coastline of 1,800 km, climate change is an issue for the country, but according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, Vietnam “aims to produce 10.7 percent of electricity from renewable sources by 2030.”

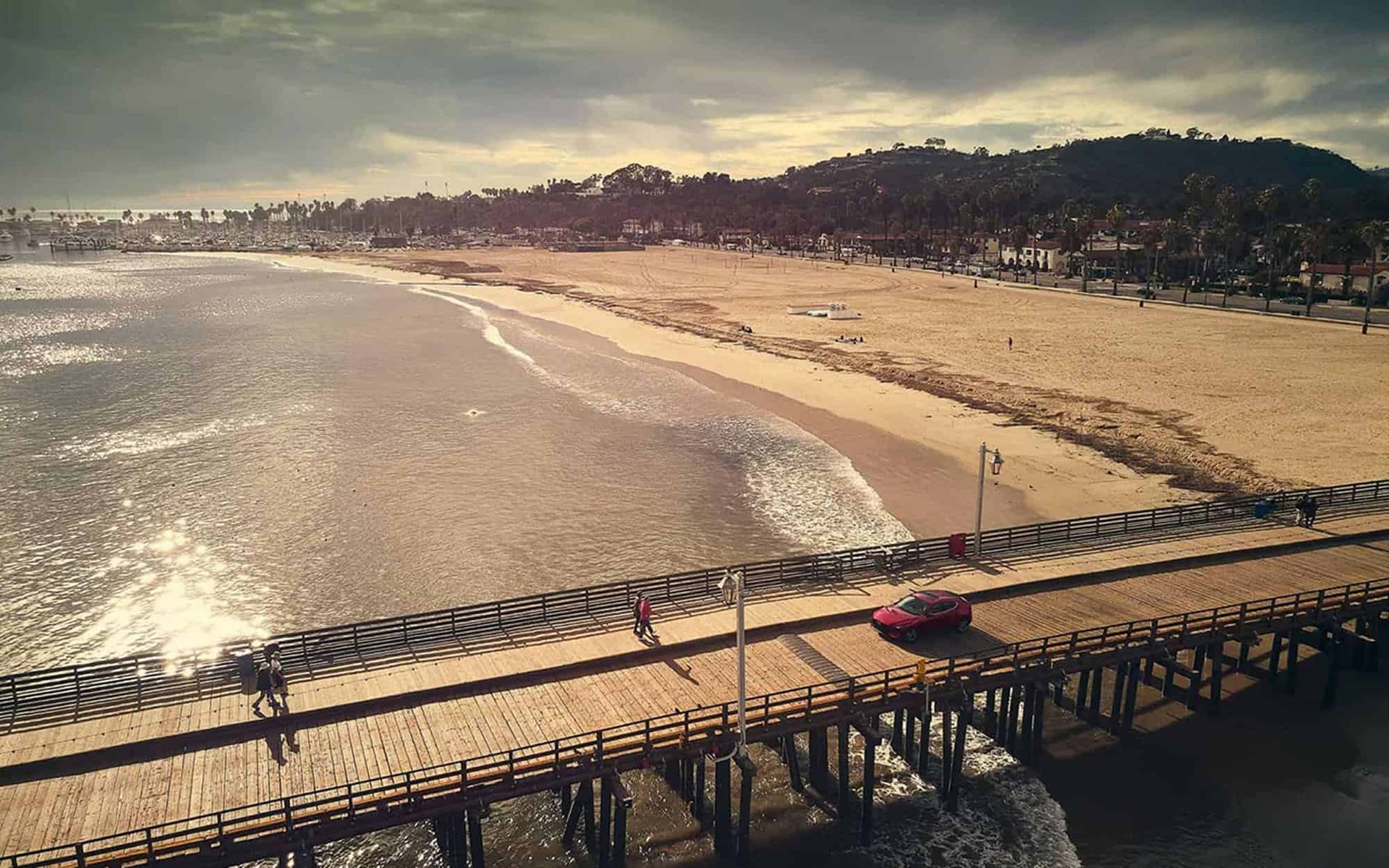

We arrive in Da Nang, but can’t resist the chance to head 20 minutes up the coast to tackle the famous Hai Van Pass. The road is a blend of tight mountain turns, sudden straights and stunning scenery, the sky and South China Sea framing Da Nang’s skyscrapers to the southeast. The pass was once the main road north to Hue, but rising traffic levels due to the country’s growth meant that in 2005 it was replaced by the more direct Hai Van Tunnel.

The undoubted highlight of any road trip across Vietnam is the mountainous Hai Van Pass, a historically important, dramatic piece of road that connects the north and south of the country. Swirling mists rising from the sea give it an otherworldly vibe.

Today, the 20 km road is the playground of the driving enthusiast, and thrums with a wild variety of vehicles enjoying the drive and scenery. Near the top of the pass, a collection of small shops nestle below a number of concrete bunkers, allegedly built by the French but apparently used by U.S. forces during the Vietnam War. Bullet holes riddle the structures, and bear testament to the fighting the area experienced. Before we make our way into town, we relish the opportunity to put the car through its paces and enjoy its superb driving dynamics.

In Da Nang, we find a microcosm of all that has made Vietnam a success over the past three decades. In 2019, it beat cities in 24 other countries to win the ASOCIO (Asian-Oceanian Computing Industry Organization) Smart City Award, which considers a city’s “happiness index, smart infrastructure, economic growth, education and development research.” Tourism is booming (there are 22 daily flights from South Korea), as is construction, with large chunks of shoreline earmarked for five-star development.

“A positive vibe is apparent everywhere in Da Nang, from the astonishing stone workshops at the Marble Mountains to the Han River.”

Taking in the extraordinary stone workshops at the Marble Mountains, with their rows of colossal figures, I’m amazed at how deftly Vietnam blends tradition with the future. Along the Han River at twilight, pleasure boats coated in colourful neon lights chug up and down the waterway, passing under garishly lit bridges. One, shaped like a dragon, breathes fire. The positive, friendly vibe we have encountered everywhere in Vietnam permeates. People go about their Saturday night and I consider what the country has achieved and the challenges it faces.

Yes, Vietnam’s transition has been remarkable, but whether it can be sustained is another matter, and the government will have to redouble its efforts to consolidate its achievements and develop the country further. It will be fascinating seeing how the story evolves, but judging on past performance, you wouldn’t bet against it.

The Mazda CX-5 proved an invaluable companion in Vietnam. It performed flawlessly in the mayhem of a Ho Chi Minh City commute and was a joy to drive down Southeast Asia’s most famous driving road, the Hai Van Pass. The 2020 model introduced paddle-shift gear changing and an eight-inch infotainment screen. Both enhanced our experience on the road.

Words Tommy Melville / Images Craig Easton

Mazda CX-5 shown not to Canadian specification.

find out more

Effortless performance

The Mazda CX-5 is an SUV at home on and off the beaten track